ROS Asks

ROS asks, “How hard are we working the income statement to produce a profit?

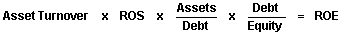

Multiplied together, ROS and asset turnover produce ROA, which asks, “How hard are we working the assets to produce a profit?”

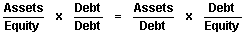

Leverage is such an important idea that the various stakeholders—debt holders, equity holders, and management —prefer different formulas to define it. Note that:

If we plug this leverage definition into the ROE formula we see

Equity holders prefer  , “how much assets do we have for every dollar of equity?” Equity holders prefer bigger values, provided that the investments are good ones. Their reasoning goes, “management’s job is to identify high return investments. For example, if they find investments for my money that return 25%, they should invest my money, and they should borrow as much as they can at 10%, so that I get the other 15% on the lender’s money, too.”

, “how much assets do we have for every dollar of equity?” Equity holders prefer bigger values, provided that the investments are good ones. Their reasoning goes, “management’s job is to identify high return investments. For example, if they find investments for my money that return 25%, they should invest my money, and they should borrow as much as they can at 10%, so that I get the other 15% on the lender’s money, too.”

Debt holders prefer  , “how much assets do we have for every dollar of debt?” They also prefer bigger numbers. At $1 assets for every $1 of debt, or 1.0 the entire company is funded by debt. At 2.0, then there is a dollar of equity for every dollar of debt, and their risk falls. Their reasoning goes, “sure, I want to lend money, but there is a chance the company will fail. If so, we can sell the assets and recover our principal. Unfortunately, we will be lucky to get some fraction for each dollar of assets, say $.50 for each dollar of assets. In that case, we get the $.50, and the equity holder gets nothing.”

, “how much assets do we have for every dollar of debt?” They also prefer bigger numbers. At $1 assets for every $1 of debt, or 1.0 the entire company is funded by debt. At 2.0, then there is a dollar of equity for every dollar of debt, and their risk falls. Their reasoning goes, “sure, I want to lend money, but there is a chance the company will fail. If so, we can sell the assets and recover our principal. Unfortunately, we will be lucky to get some fraction for each dollar of assets, say $.50 for each dollar of assets. In that case, we get the $.50, and the equity holder gets nothing.”

Managers prefer  . At 1.0, there is a dollar of debt for every dollar of equity. At 2.0, there are two dollars of debt for every dollar of equity. Managers want to keep their jobs, and in that regard they face two risks. If the company cannot meet its interest obligations, debt holders can force the company into receivership and fire management. On the other hand, if a public company has little leverage, it becomes a takeover target.

. At 1.0, there is a dollar of debt for every dollar of equity. At 2.0, there are two dollars of debt for every dollar of equity. Managers want to keep their jobs, and in that regard they face two risks. If the company cannot meet its interest obligations, debt holders can force the company into receivership and fire management. On the other hand, if a public company has little leverage, it becomes a takeover target.

The key questions are, “who gets the wealth that is being created?”, and “who takes the risk of failure?”

Return On Equity

Return On Equity