In any month, a product’s demand is driven by its monthly customer survey score. Assuming it does not run out of inventory, a product with a higher score will outsell a product with a lower score.

Customer survey scores are calculated 12 times a year. The December customer survey scores are reported in the Capstone Courier’s Segment Analysis pages.

A customer survey score reflects how well a product meets its segment’s buying criteria. Company promotion, sales and accounts receivable policies also affect the survey score.

Scores are calculated once each month because a product’s age and positioning change a little each month. If during the year a product is revised by Research and Development, the product’s age, positioning and MTBF characteristics can change quite a bit. As a result, it is possible for a product with a very good December customer survey score to have had a much poorer score – and therefore poorer sales – in the months prior to an R&D revision.

Prices, set by Marketing at the beginning of the year, will not change during the year.

3.1 Buying Criteria and the Customer Survey Score

The customer survey starts by evaluating each product against the buying criteria. Next, these assessments are weighted by the criteria’s level of importance. For example, some segments assign a higher importance to positioning than others. A well-positioned product in a segment where positioning is important will have a greater overall impact on its survey score than a well-positioned product in a segment where positioning is not important (see 3.2 Estimating the Customer Survey Score).

A perfect customer survey score of 100 requires that the product: Be positioned at the ideal spot (the segment drifts each month, so this can occur only one month per year); be priced at the bottom of the expected range; have the ideal age for that segment (unless they are revised, products grow older each month, so this can occur only one month per year); and have an MTBF specification at the top of the expected range.

Your customers want perfection, but it is impractical to have a perfect product, and the more “perfect” the product, the higher its costs. Your task is to give customers great products while still making a profit. Your competitors face the same dilemma.

3.1.1 Positioning Score

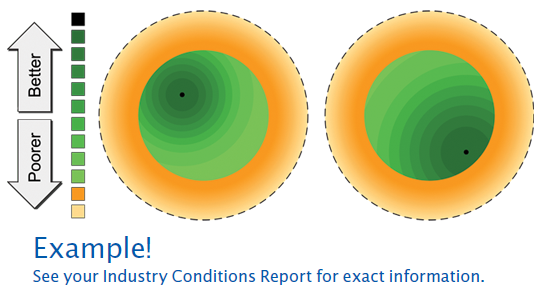

Conceptually, a segment is defined by customers saying, “I want this (whatever ‘this’ is), but within limits.” It is vital for marketers to understand both what the customers want and their boundaries. The Perceptual Map captures these ideas with circles. Each segment is described with a dashed outer circle, a solid inner circle, and a dot we call the ideal spot.

The dashed outer circle defines the outer limit of the segment. Customers are saying, “I will NOT purchase a product outside this boundary.” We call the dashed circle “the rough cut circle” because any product beyond it “fails the rough cut” and is dropped from consideration. However, a product just inside the circle does not mean customers are delighted. A product near the outer limit is badly positioned.

The solid inner circle defines the heart of the segment. Customers want products in the heart of segment. We call the solid circle “the fine cut” because products within it “make the fine cut.”

The ideal spot is that point in the heart of the segment where, all other things being equal, demand is highest.

We call the orange boundary areas in Figure 3.1 “the rough cut area.” The green areas represent “the fine cut area.” The black dots are the ideal spots.

The segment is moving across the Perceptual Map a little each month. In a perfect world your product would be positioned in front of the ideal spot in January, on top of the ideal spot in June, and trail the ideal spot in December. In December it would complete an R&D project to jump in front of the ideal spot for next year.

Positioning in the Rough Cut Area

What happens to products that plot in the rough cut area? These products are badly positioned. Customers will consider them, but they are at a significant disadvantage to products inside the fine cut circle.

Specifically, products inside the rough cut have reduced customer survey scores. Their customer survey score drops in a linear fashion. Just beyond the fine cut circle the score drops 1%. Halfway between the fine and rough cut circles the score drops 50%. The customer survey score drops 99% for products that are just inside the rough cut circle.

Sensors that are about to enter the orange areas can be revised by Research & Development see (4.1.1 Changing Performance, Size and MTBF).

The location of each segment’s rough cut circle as of December 31 of the previous year appears on page 11 of the Courier.

Positioning Inside the Fine Cut

In Figure 3.1, products that plot within 2.5 units of the center of the segment are inside the green, fine cut circles. Ideal spots for each segment are illustrated by the black dots. The example on the left illustrates a segment that wants proven, inexpensive technology. The ideal spot trails the segment, where material costs are lower. The example on the right illustrates a segment that wants cutting-edge technology. The ideal spot is located towards the leading edge of the circle, where size is smaller and performance is faster.

Participants often ask, “Why are some ideal spots ahead of the segment centers?” The segments are moving. From a customer’s perspective, if they buy a product at the ideal spot, it will still be a cutting edge product when it wears out. For contrast, if they buy a product at the trailing edge, it will not be inside the segment when it wears out.

A product’s positioning score changes each month because segments and ideal spots drift a little each month. Placing a product in the path of the ideal spot will return the greatest benefit though the course of a year.

3.1.2 Pricing

Every segment has a $10.00 price range. Price ranges in all segments drop $0.50 per year.

Segment price expectations correlate with the segment’s position on the Perceptual Map. Segments that demand higher performance and smaller sizes are willing to pay higher prices.

Price ranges for Round 0 (the year prior to Round 1) are published in the Segment Analysis pages of the Capstone Courier.

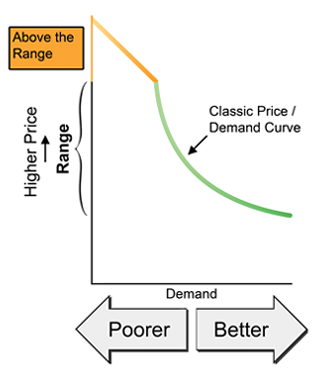

Price Rough Cut

Sensors priced $5.00 above the segment guidelines will not be considered for purchase. Those products fail the price rough cut.

Sensors priced $1.00 above the segment guidelines lose about 20% of their customer survey score (orange lines, Figure 3.2). Sensors continue to lose approximately 20% of their customer survey score for each dollar above the guideline, on up to $4.99, where the score is reduced by approximately 99%. At $5.00 above the range, demand for the product is zero.

Price Fine Cut

Within each segment’s price range, price scores follow a classic economic demand curve (green bow, Figure 3.2): As price goes down, the price score goes up.

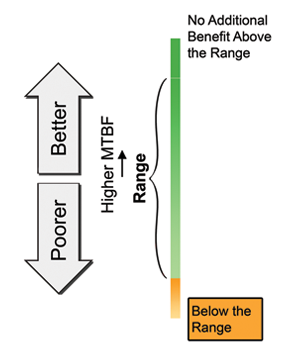

3.1.3 MTBF Score

Each segment sets a 5,000 hour range for MTBF (Mean Time Before Failure), the number of hours a product is expected to operate before it malfunctions.

MTBF Rough Cut

Demand scores fall rapidly for products with MTBFs beneath the segment’s guidelines. Products with an MTBF 1,000 hours below the segment guideline lose 20% of their customer survey score. Products continue to lose approximately 20% of their customer survey score for every 1,000 hours below the guideline, on down to 4,999 hours, where the customer survey score is reduced by approximately 99%. At 5,000 hours below the range, demand for the product falls to zero.

MTBF Fine Cut

Within the segment’s MTBF range, the customer survey score improves as MTBF increases (Figure3.3). However, material costs increase $0.30 for every additional 1000 hours of reliability. Customers ignore reliability above the expected range– demand plateaus at the top of the range.

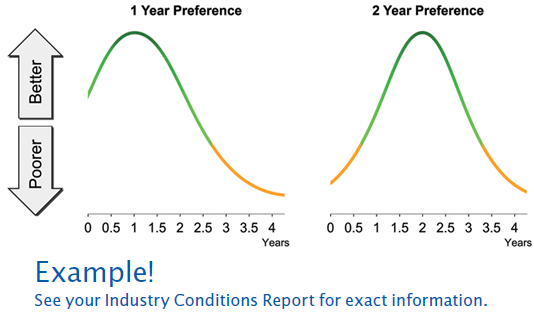

3.1.4 Age Score

The age criteria does not have a rough cut; a product will never be too young or too old to be considered for purchase.

Segments that want cutting-edge technology prefer newer products– the ideal ages for these segments are generally less than one and a half years. Other segments prefer proven technology. These segments seek older designs.

Each month, customers assess a product’s age and award a score based upon their preferences. Examples of age preferences are illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Age preferences for each segment are published in the Industry Conditions Report and the Segment Analysis pages of the Capstone Courier.

3.2 Estimating the Customer Survey Score

The customer survey score drives demand for your product in a segment. Your demand in any given month is your score divided by the sum of the scores. For example, if your product’s score in April is 20, and your competitors’ scores are 27, 19, 21, and 3, then your product’s April demand is:

20/(20+27+19+21+3) = 22%

Assuming you had enough inventory to meet demand, you would receive 22% of segment sales for April.

What generates the score itself? Marketers speak of “the 4 P’s” – price, product, promotion and place. Price and product are found in the buying criteria. Together they present a price-value relationship. Your promotion budget builds “awareness,” the number of customers who know about your product before shopping. Your sales budget (place) builds “accessibility,” the ease with which customers can work with you after they begin shopping. To the 4 P’s we can add two additional elements– credit terms and availability. Credit terms are expressed by your accounts receivable policy. Availability addresses inventory shortages.

To estimate the customer survey score, begin with the buying criteria available in the Courier’s Segment Analysis reports. For example, suppose the buying criteria are:

- Age, 2 years– importance: 47%

- Price, $20.00-$30.00– importance: 23%

- Ideal Position, performance 5.0 size 15.0– importance: 21%

- MTBF, 14,000-19,000– importance: 9%

A perfect score of 100 requires that the product have an age of 2.0 years, a price of $20.00, positioning at the ideal spot (5.0 and 15.0), and an MTBF of 19,000 hours.

Observe that the segment weighs the criteria at: Age 47%, Price 23%, Positioning 21%, and MTBF 9%. You can convert these percentages into points. Price is worth 23 points. The perfect Round 0 price of $20.00 gets 23 points, but at the opposite end of the price range, a price of $30.00 would get only one point. Therefore, you can use the figures that describe the buying criteria to estimate a base score for a product.

However, the base score can fall because of poor awareness (promotion), accessibility (place), or the credit terms you extend to your customers.

3.2.1 Accounts Receivable

A company’s accounts receivable policy sets the amount of time customers have to pay for their purchases. At 90 days there is no reduction to the base score. At 60 days the score is reduced 0.7%. At 30 days the score is reduced 7%. Offering no credit terms (0 days) reduces the score by 40% (see 4.4.5 Credit Policy).

3.2.2 Awareness

Awareness is built over time by the product’s promotion budget. Promotion budgets are put towards advertising and public relations campaigns.

Suppose your product has not been promoted for many years while a competitor has aggressively promoted its product. Your awareness is 0%, their awareness is 100%. If you and your competitor’s products are otherwise identical, your product’s survey score will be half the score of the competitor’s.

A product with 0% awareness loses half its base score. At 50% awareness, it loses 25% of its base score. At 100% awareness it keeps its entire base score. Mathematically this expresses itself as:

[(1+awareness)/2] * base score

A product with 0% awareness does not have 0% demand. Consider a world where all products had 0% awareness. Customers need products. They would search until they found products that met their criteria. But in this world, suppose a mediocre product had 100% awareness. It would have a significant advantage against similar products. Awareness, then, affects the competitive rivalry. It reduces search costs for customers, and increases costs for vendors.

3.2.3 Accessibility

Accessibility is built over time by the product’s sales budget. Sales budgets are put towards salespeople and distribution systems.

For estimating the impact upon the customer survey score, accessibility works like awareness. However, the processes for building awareness and accessibility are quite different: Awareness is concerned with “before the sale;” accessibility is concerned with “during and after the sale.”

A product with 0% accessibility loses half its base score. At 50% accessibility, it loses 25% of its base score. At 100% accessibility it keeps its entire base score. Mathematically this expresses itself as:

[(1+ accessibility)/2] * base score

Like awareness, 0% accessibility does not imply zero sales. The arguments parallel those presented for awareness. Accessibility affects the competitive rivalry. It reduces acquisition costs for customers, and increases costs for vendors.

See 4.2 Marketing for more information on awareness and accessibility.

3.3 Stock Outs and Seller’s Market

What happens when a product generates high demand but stocks out? The unmet demand is divided between the remaining products in proportion to their customer survey scores. This could happen in any month. To assist with diagnosing stock outs and their impacts, see the Market Share Report on page 10 of the Capstone Courier.

Usually, a product with a low customer survey score has low sales. However, if a segment’s demand exceeds the supply of products available for sale, a seller’s market emerges. In a seller’s market, customers will accept low scoring products as long as they fall within the segment’s rough cut limits. For example, desperate customers with no better alternatives will buy:

- A product positioned just inside the rough cut circle on the Perceptual Map– outside the circle they say “no” to the product;

- A product priced $4.99 above the price range– at $5.00 customers reach their tolerance limit and refuse to buy the product;

- A product with an MTBF 4,999 hours below the range– at 5,000 hours below the range customers refuse to buy the product.

Watch out for three common tactical mistakes in a seller’s market:

- After completing a capacity analysis, a team decides that industry demand exceeds supply. They price their product $4.99 above last round’s published price range, forgetting that price ranges fall by $0.50 each round. Demand for the product becomes zero. They should have priced $4.49 above last year’s range.

- A team disregards products that are in the positioning rough cut. These products normally can be ignored because they have low customer survey scores. However when the team increases the price, the customer survey score falls below the products in the rough cut areas, which are suddenly more attractive than their product.

- The company fails to add capacity for the next round. Typically a seller’s market appears because a competitor unexpectedly exits a segment. This creates a windfall opportunity for the remaining competitors. However it is easy to demonstrate that a company should always have enough capacity to meet demand from its customers. (Consider the question, “What happens to price if every competitor has just enough capacity to meet demand from its customers?”).

How can you be sure of a seller’s market? You can’t, unless you are certain that industry capacity, including a second shift, cannot meet demand for the segment. In that case even very poor products will stock out as customers search for anything that will meet their needs.